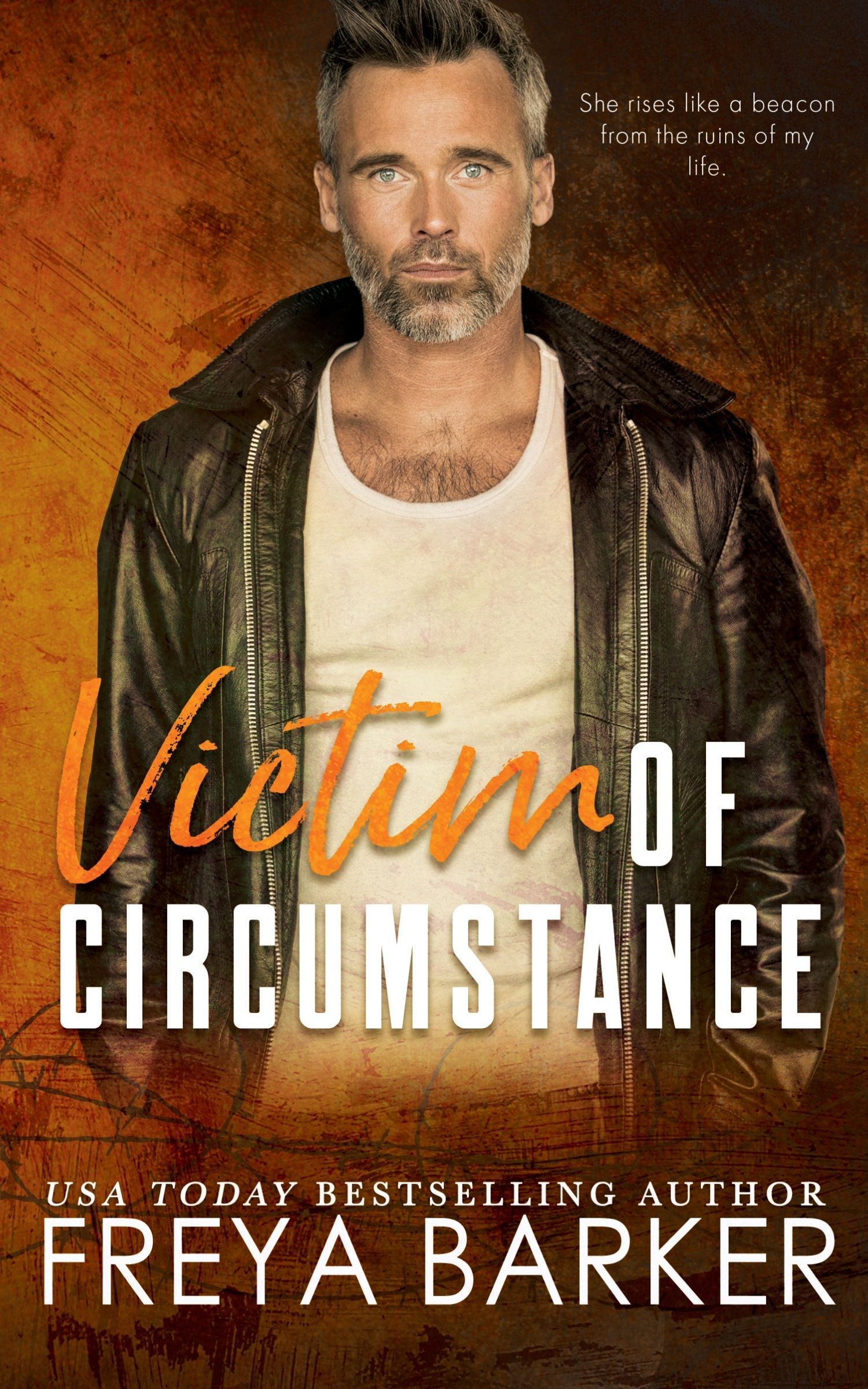

Victim Of Circumstance

They didn’t know each other, but the events of one single day heralded a pivotal change that would alter their lives forever.

Almost two decades spent locked away in a dark, dank cell, Gray Bennet isn’t used to the sun, the sounds, the scents.

It’s overwhelming.

Each year Robin Bishop returns, and while everyone around her is solemn, she lifts her face to the sun and celebrates her freedom.

It’s liberating.

He sees her.

She stands out in the grieving crowd—her head thrown back, her face bright with contentment—like a beacon offering to guide him into the light.

Fresh air.

I stop when I hear the harsh clank of the gate closing behind me and suck in a deep, desperate breath. It’s like my lungs are able to expand fully for the first time in eighteen years. The full hit of oxygen makes me instantly lightheaded.

It’s all between my ears, I realize that, but there’s no denying the physical impact breathing actual free air after so many years has on me. I force myself not to bend over and gasp, like my body wants to. Instead I raise my eyes to a mostly cloudless sky, giving my senses a moment to adjust.

The shrill honk of a car horn interrupts my efforts to calibrate my senses and my eyes automatically dart to the end of the wide drive into Rockwood Penitentiary, where I’ve spent almost two decades in Cell Block C. My cab is waiting for me and I slowly start walking toward it, almost expecting a harsh voice to call me back.

All I have is a paper bag with the few meager, and by now meaningless, belongings I had on me when I was brought here. My clothes feel weird and unfamiliar, taken from a supply closet with stacks of unclaimed street clothes for people like me who have no one on the outside to send them some. I don’t know where the clothes I was wearing back then disappeared to. Maybe some other guy wore those home.

Home. A weird concept, even before I ended up here it was an undefined place. At that time I had a tiny, rented studio apartment, but for two decades home had been a six-by-eight prison cell. Small, but it was mine. I didn’t have much to fill it with except for the books given to me through Books to Prisoners, one of the many organizations trying to make life behind bars more livable.

I have eighteen books, one for each year I spent inside. Books I read over and over and over again. There’d been more, some borrowed from the prison library, but these eighteen came to mean something to me. They were representative of every year I spent inside. The ones that allowed me to disappear, even just for the time it took me to read them. They’d been my true sanctuary, my peaceful haven in an oppressive, sound-filled environment.

They’re all in my paper bag, making it heavy as fuck to carry. Also in there are my toothbrush, my soap, and a leather wristband I forgot I had until it was handed to me earlier. My leather jacket, the only item of my own clothing remaining, is hot on my back in the midday sun. The wad of cash, both the hundred and fifteen dollars I had on me when I was arrested, and the gate money—a few weeks’ worth of living expenses I’m supposed to pay back in a few months—are burning a hole in my pocket.

“Where are you heading?” the old man standing beside the taxi asks when I approach.

Isn’t that the million-dollar question? One I don’t have an answer for right away—it’s been so long since I’ve had to make any decisions—so I buy myself some time by answering, “The closest bus station.”

Clutching my paper bag, I climb in the back seat and immediately open the window, wanting to feel the air move on my face.

“Is that okay?” I ask politely.

“Sure,” he says, climbing behind the wheel. “You’re not the only one who does that.”

I don’t talk much. Never have, and certainly not while I was inside. I kept mostly to myself. I’m relieved when the driver doesn’t make an effort to engage in small talk.

I look out the window, letting the landscape roll by as I consider where I might want to go. Big cities where I can disappear anonymously pass my mind’s eye, but during the twenty-minute ride, the one place that keeps coming to the forefront is my hometown of Beaverton.

It seems crazy to go back to a small town where most people will remember what you did, but somehow I find myself compelled to ask for a ticket there when I walk up to the window at the bus station.